Cell Defense: The Plasma Membrane ౼ An Overview

Cells, the fundamental units of life, rely on the plasma membrane for protection; it controls molecular passage and defends against external threats, crucial for survival.

Cellular defense is paramount for organismal survival, and the plasma membrane stands as the first line of protection. This dynamic barrier isn’t merely a passive enclosure; it actively regulates what enters and exits the cell, shielding it from harmful pathogens and maintaining internal homeostasis.

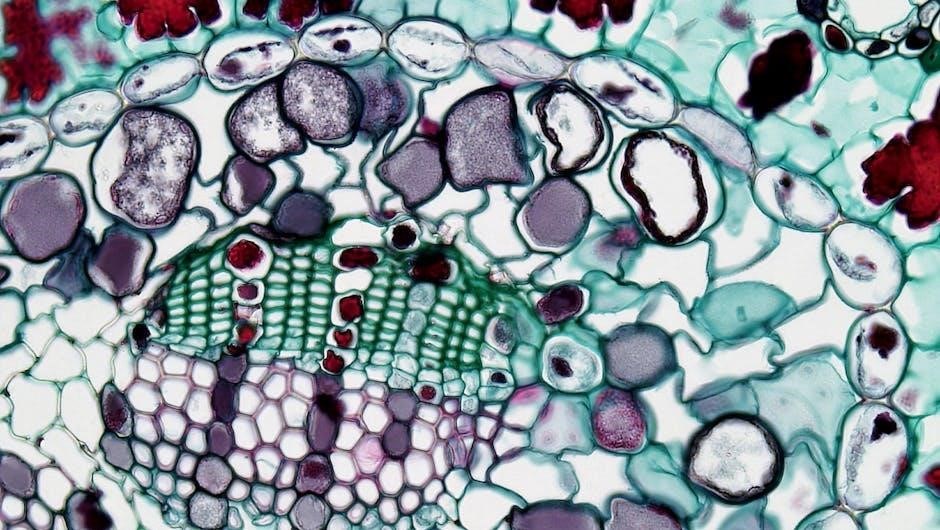

Understanding the membrane’s structure – a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins – is key to grasping its defensive capabilities. Eukaryotic cells, with their complex internal organization including a nucleus, rely heavily on this membrane for compartmentalization and protection. Prokaryotic cells, lacking a nucleus, similarly depend on the plasma membrane for survival in diverse environments.

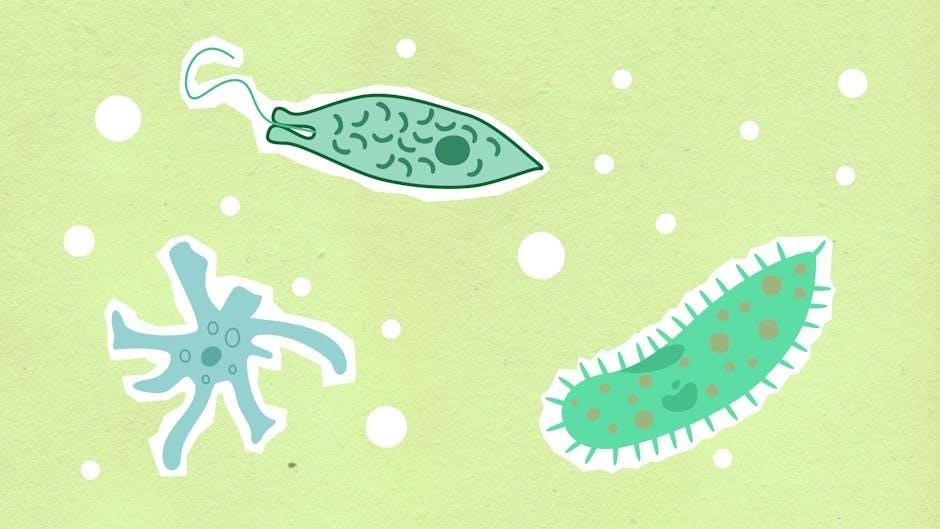

The membrane’s selective permeability allows essential nutrients to enter while preventing the intrusion of damaging substances. This intricate control is vital, as cells are constantly bombarded by external challenges. From microscopic bacteria to viruses, the plasma membrane plays a critical role in recognizing and responding to these threats, initiating defense mechanisms to ensure cellular integrity.

The Plasma Membrane: A Cellular Barrier

The plasma membrane functions as a selective barrier, defining the cell’s boundaries and meticulously controlling the passage of substances. Composed primarily of a phospholipid bilayer, it presents a hydrophobic core that restricts the free flow of water-soluble molecules. This inherent structure is fundamental to maintaining cellular integrity and protecting the internal environment.

This barrier isn’t absolute; membrane proteins facilitate the transport of specific molecules, acting as gatekeepers and channels. These proteins are crucial for nutrient uptake, waste removal, and cell signaling. The membrane’s fluidity, influenced by cholesterol content, allows for dynamic adjustments in response to environmental changes, enhancing its protective capabilities.

Furthermore, glycolipids and glycoproteins on the cell surface contribute to cell recognition and interaction, aiding in immune responses and defense against pathogens. Essentially, the plasma membrane isn’t just a wall, but a sophisticated security system safeguarding the cell’s delicate internal machinery.

Plasma Membrane Structure

Plasma membranes comprise a phospholipid bilayer with embedded proteins and cholesterol, alongside glycolipids and glycoproteins, forming a dynamic, fluid mosaic.

Phospholipid Bilayer: The Foundation

The phospholipid bilayer forms the core structural component of the plasma membrane, acting as a selective barrier. These phospholipids are amphipathic molecules, meaning they possess both hydrophilic (water-attracting) and hydrophobic (water-repelling) regions. The hydrophilic heads face outwards, interacting with the aqueous environments both inside and outside the cell, while the hydrophobic tails cluster inwards, away from water.

This arrangement creates a stable, self-sealing barrier that restricts the passage of many substances. The fluidity of the bilayer is crucial for membrane function, allowing proteins to move laterally and facilitating processes like cell signaling and transport. This foundational structure is essential for maintaining cellular integrity and regulating what enters and exits the cell, directly contributing to its defense mechanisms. The bilayer’s composition influences its permeability and overall defensive capabilities.

Membrane Proteins: Diverse Functions

Membrane proteins are integral to the plasma membrane’s functionality, performing a vast array of tasks beyond simply providing structural support. They mediate cellular communication, transport molecules, and play critical roles in cell recognition and defense. These proteins are not uniformly distributed; their arrangement contributes to specialized membrane domains.

Proteins act as channels or carriers, facilitating the passage of specific molecules across the hydrophobic lipid bilayer. Others function as receptors, binding to signaling molecules and initiating cellular responses. Crucially, some membrane proteins are involved in identifying and responding to external threats, like pathogens. Their diversity allows the membrane to dynamically adapt to changing conditions and maintain cellular homeostasis, bolstering the cell’s defensive capabilities against a constantly changing environment. They are essential for a cell’s survival.

Integral Proteins: Embedded within the Membrane

Integral proteins are permanently embedded within the plasma membrane’s lipid bilayer, possessing hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions that interact with both the lipid core and the aqueous environments inside and outside the cell. These proteins often span the entire membrane, functioning as channels, carriers, or receptors. Their firm integration provides structural stability and allows for the transport of molecules that cannot readily cross the lipid barrier.

Many integral proteins are crucial for cellular defense, acting as gatekeepers controlling what enters and exits the cell. Some recognize specific molecules on pathogens, triggering immune responses. Others form channels allowing signaling molecules to initiate defensive cascades. Their embedded nature allows them to directly interact with the membrane environment, influencing its fluidity and function, ultimately safeguarding the cell’s integrity and promoting survival against external threats.

Peripheral Proteins: Associated with the Surface

Peripheral proteins differ from integral proteins as they do not embed themselves within the plasma membrane’s hydrophobic core. Instead, they associate with the membrane surface, often binding to integral proteins or the polar head groups of phospholipids. These proteins play vital roles in cell signaling, enzymatic activity, and maintaining cell shape, contributing significantly to cellular defense mechanisms.

Many peripheral proteins participate in immune responses by activating signaling pathways upon detecting external threats. They can also act as structural components, reinforcing the membrane and providing resilience against physical stress. Furthermore, some peripheral proteins are involved in cell adhesion, enabling cells to interact with each other and form protective barriers. Their dynamic association with the membrane allows for rapid responses to changing environmental conditions, bolstering the cell’s defense capabilities.

Cholesterol: Maintaining Membrane Fluidity

Cholesterol, a lipid molecule, is a crucial component of animal cell plasma membranes, playing a vital role in regulating membrane fluidity. At higher temperatures, it restrains phospholipid movement, reducing fluidity and increasing stability. Conversely, at lower temperatures, cholesterol prevents tight packing of phospholipids, maintaining fluidity and preventing the membrane from becoming too rigid. This dynamic regulation is essential for proper membrane function and, consequently, cellular defense.

Maintaining optimal fluidity is critical for the function of membrane proteins involved in defense, such as receptors and transport proteins. A fluid membrane allows these proteins to move laterally and interact effectively, enabling rapid responses to external threats. Cholesterol also influences membrane permeability, impacting the entry of pathogens and the exit of signaling molecules. Proper membrane fluidity, therefore, is a cornerstone of effective cellular defense mechanisms, ensuring the cell can adapt and survive in changing environments.

Glycolipids and Glycoproteins: Cell Recognition

Glycolipids and glycoproteins, found on the outer surface of the plasma membrane, are essential for cell recognition and play a significant role in cellular defense. These molecules have carbohydrate chains attached to lipids (glycolipids) or proteins (glycoproteins), forming a unique “sugar coating” called the glycocalyx. This coating acts like a cellular fingerprint, allowing cells to identify each other and distinguish between “self” and “non-self”.

In the context of defense, this recognition capability is vital for the immune system. Glycoproteins can act as receptors for signaling molecules released during immune responses, triggering defensive actions. They also help immune cells identify infected or cancerous cells. Furthermore, alterations in glycosylation patterns can signal cellular stress or disease. The precise carbohydrate structures are crucial for accurate cell-cell communication and effective immune surveillance, contributing significantly to overall cellular defense.

Plasma Membrane Permeability

Plasma membrane permeability dictates what enters and exits the cell, a critical aspect of defense; selective passage controls the internal environment and protects against threats.

Selective Permeability: Controlling Entry and Exit

The plasma membrane’s selective permeability is paramount for cellular defense, meticulously regulating the passage of substances. This isn’t a free-for-all; the membrane acts as a gatekeeper, allowing essential nutrients to enter while preventing harmful pathogens and toxins from breaching the cellular boundary. This control is achieved through the unique structure of the phospholipid bilayer and the embedded proteins.

Small, nonpolar molecules like oxygen and carbon dioxide readily diffuse across the membrane, while larger, polar molecules, and ions require assistance. This selective nature ensures the cell maintains its internal environment, vital for proper function and defense against external stressors. The membrane’s ability to discriminate between molecules is fundamental to its protective role, safeguarding the cell’s integrity and enabling it to respond effectively to its surroundings. Ultimately, selective permeability is a cornerstone of cellular survival.

Passive Transport: No Energy Required

Passive transport mechanisms allow molecules to traverse the plasma membrane without expending cellular energy, relying instead on concentration gradients and the inherent properties of the membrane. This is crucial for efficient nutrient uptake and waste removal, contributing to cellular defense by maintaining optimal internal conditions.

Simple diffusion involves the movement of substances directly across the phospholipid bilayer, down their concentration gradient – from areas of high concentration to low concentration. Facilitated diffusion, however, utilizes membrane proteins to assist in the transport of larger or polar molecules that cannot easily cross the lipid bilayer. Both methods are vital for maintaining cellular homeostasis and bolstering defense mechanisms by ensuring a constant supply of necessary resources and eliminating potentially harmful substances, all without energy expenditure.

Simple Diffusion: Movement Down the Concentration Gradient

Simple diffusion is a fundamental process where substances move across the plasma membrane from an area of high concentration to one of low concentration, requiring no cellular energy expenditure. This passive transport relies on the inherent kinetic energy of molecules and the permeability of the lipid bilayer.

Small, nonpolar molecules like oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) readily diffuse across the membrane, playing a critical role in cellular respiration and waste removal – essential components of cellular defense. The rate of diffusion is influenced by factors such as temperature, pressure, and the concentration gradient itself. This process ensures cells receive necessary gases and eliminate metabolic byproducts, contributing to a stable internal environment and bolstering resistance against external threats, all without active cellular intervention.

Facilitated Diffusion: Assisted by Proteins

Facilitated diffusion is a type of passive transport that aids the movement of substances across the plasma membrane, but unlike simple diffusion, it requires the assistance of membrane proteins. These proteins, either channel or carrier proteins, provide a pathway for molecules that cannot easily cross the lipid bilayer on their own.

This process is crucial for transporting polar or charged molecules, like glucose and amino acids, which are vital for cellular function and defense. Channel proteins create pores, while carrier proteins bind to the molecule and change conformation to shuttle it across. Facilitated diffusion doesn’t require energy, still moving substances down their concentration gradient, but enhances the cell’s ability to acquire essential nutrients and maintain internal homeostasis, strengthening its defense mechanisms against external challenges.

Active Transport: Energy is Required

Active transport mechanisms are essential when a cell needs to move substances against their concentration gradient – from an area of low concentration to one of high concentration. This process fundamentally requires cellular energy, typically in the form of ATP (adenosine triphosphate). Unlike passive transport, active transport doesn’t simply rely on diffusion.

This energy expenditure allows cells to maintain internal conditions drastically different from their surroundings, a critical aspect of cellular defense. Two primary forms exist: primary active transport, directly using ATP, and secondary active transport, utilizing an electrochemical gradient established by primary transport. Examples include the sodium-potassium pump, vital for nerve impulse transmission and maintaining cell volume, and endocytosis/exocytosis for bulk transport of larger molecules, bolstering the cell’s protective capabilities.

Sodium-Potassium Pump: Maintaining Cellular Potential

The sodium-potassium pump is a quintessential example of primary active transport, tirelessly working to maintain the electrochemical gradient across the plasma membrane. This integral membrane protein utilizes ATP to pump three sodium ions (Na+) out of the cell for every two potassium ions (K+) pumped in.

This seemingly simple exchange is profoundly important for several cellular functions, including nerve impulse transmission, muscle contraction, and regulating cell volume. Crucially, maintaining this potential is a key defense mechanism. It allows cells to rapidly respond to stimuli and maintain a stable internal environment, resisting disruptions from external threats. Disruptions to the pump’s function can lead to cellular dysfunction and even cell death, highlighting its vital role in cellular survival and defense.

Endocytosis and Exocytosis: Bulk Transport

Endocytosis and exocytosis are vital processes for moving large molecules, or bulk amounts of substances, across the plasma membrane – processes essential for cellular defense and communication. Endocytosis involves the cell engulfing material from the external environment by invaginating the plasma membrane, forming vesicles. This can be used to internalize pathogens or cellular debris, effectively removing threats.

Conversely, exocytosis is the process where vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing their contents outside the cell. This is crucial for secreting signaling molecules, antibodies, or waste products. Both processes require energy and are tightly regulated, ensuring efficient and targeted transport. These bulk transport mechanisms are fundamental to immune responses and maintaining cellular homeostasis, bolstering the cell’s defensive capabilities.

Cellular Defense Mechanisms

Cells employ diverse strategies to combat external threats, including physical barriers and intricate defense responses orchestrated by the plasma membrane for survival.

Protecting Against External Threats

Cells constantly face a barrage of external threats, ranging from pathogens like bacteria and viruses to toxins and physical damage. The plasma membrane serves as the first line of defense, a selective barrier preventing unrestricted entry of harmful substances. This membrane isn’t merely a passive wall; it actively participates in recognizing and responding to threats.

Pathogens often attempt to breach cellular defenses, but the membrane’s structure hinders their access. Its hydrophobic core resists the passage of water-soluble molecules, effectively blocking many invaders. Furthermore, the membrane’s fluidity allows it to quickly seal breaches and adapt to changing conditions. Specialized proteins embedded within the membrane act as sentinels, detecting the presence of foreign entities and initiating defense cascades. These mechanisms are vital for maintaining cellular integrity and overall organism health, ensuring survival against a hostile external environment.

The Role of the Plasma Membrane in Defense

The plasma membrane plays a pivotal role in cellular defense, functioning as both a physical barrier and a dynamic signaling hub; It restricts the entry of pathogens and harmful molecules while facilitating crucial communication with the external environment. Integral proteins act as receptors, binding to signaling molecules released by immune cells, triggering intracellular defense responses.

Beyond simple exclusion, the membrane participates in receptor-mediated defense. When a pathogen is detected, receptors activate signaling pathways that initiate processes like phagocytosis or the production of antiviral proteins. Glycolipids and glycoproteins on the membrane surface contribute to cell recognition, allowing the immune system to distinguish between self and non-self. This intricate interplay between membrane structure and function is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis and protecting against a constantly evolving array of threats, ensuring the cell’s survival.

Barrier Against Pathogens

The plasma membrane serves as the first line of defense against invading pathogens, creating a physical barrier that restricts their entry into the cell. Its phospholipid bilayer structure is inherently impermeable to many harmful substances, including viruses, bacteria, and toxins. This selective permeability is crucial for maintaining the internal cellular environment and preventing infection.

Furthermore, the membrane’s composition actively hinders pathogen access. Cholesterol modulates membrane fluidity, impacting the ability of pathogens to insert themselves or disrupt membrane integrity. Membrane proteins, particularly those forming tight junctions, reinforce the barrier function, preventing pathogens from squeezing between cells. Even the glycocalyx, formed by glycolipids and glycoproteins, provides a protective layer, hindering pathogen attachment and initiating immune responses. This multi-faceted barrier ensures robust protection against a wide range of external threats.

Receptor-Mediated Defense Responses

Beyond a physical barrier, the plasma membrane actively participates in defense through receptor-mediated responses. Specialized membrane proteins function as receptors, binding to signaling molecules released by the immune system or produced in response to pathogen detection. This binding triggers intracellular signaling cascades, activating defense mechanisms.

For example, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on the membrane surface, initiating immune cell activation and inflammation. These signals can also induce changes in membrane permeability or activate transport proteins to expel harmful substances. Furthermore, receptor signaling can lead to the upregulation of antimicrobial proteins or the initiation of programmed cell death (apoptosis) to eliminate infected cells. This dynamic interplay between membrane receptors and intracellular signaling pathways is vital for a coordinated and effective immune response.

Key Concepts & Answer Key Relevance

Understanding membrane transport and structure is key; the ‘Answer Key’ assesses comprehension of these principles, vital for grasping cellular defense mechanisms and biological functions.

Understanding Membrane Transport Mechanisms

Membrane transport is fundamental to cell defense, dictating what enters and exits, maintaining internal stability. Passive transport, like simple and facilitated diffusion, requires no energy, relying on concentration gradients for molecule movement. This is crucial for nutrient uptake and waste removal, but offers limited control.

Conversely, active transport expends energy – notably via the sodium-potassium pump – to move substances against their gradients. This powers vital processes like nerve impulse transmission and maintaining cellular potential, bolstering defense. Endocytosis and exocytosis facilitate bulk transport of larger molecules, enabling cells to engulf pathogens or release signaling molecules.

Grasping these mechanisms is essential; the ‘Answer Key’ tests comprehension of how selective permeability, diffusion rates, and energy requirements impact cellular defense strategies. Understanding these processes reveals how cells actively protect themselves from external threats and maintain internal homeostasis.

Applying Knowledge to ‘Answer Key’ Questions

Successfully navigating the ‘Answer Key’ requires a firm grasp of plasma membrane function and transport mechanisms. Questions often assess understanding of selective permeability – identifying which molecules readily cross the membrane and why. Expect scenarios testing differentiation between passive (diffusion, facilitated diffusion) and active transport (sodium-potassium pump, endocytosis/exocytosis).

Critical thinking is key; questions may present novel situations demanding application of learned principles. For example, predicting how a disrupted pump affects cellular potential or analyzing the impact of membrane protein defects on defense. The ‘Answer Key’ isn’t merely about memorization, but about demonstrating comprehension of how these processes contribute to cellular survival.

Focus on relating membrane properties to real-world scenarios, like pathogen entry or nutrient acquisition. Mastering these concepts ensures a solid foundation in cell biology and a strong performance on assessments.

Further Exploration

Cell and related journals publish cutting-edge membrane biology research. Online resources and textbooks offer deeper insights into cell defense mechanisms and plasma membrane dynamics.

Resources for Deeper Learning

Numerous resources expand understanding beyond basic concepts. Textbooks specializing in cell biology, molecular biology, and immunology provide comprehensive coverage of the plasma membrane and its defensive roles. Online platforms like Khan Academy offer accessible video lessons and practice exercises, reinforcing key principles of membrane transport and cellular defense.

Scientific journals, including Cell, publish original research articles detailing the latest discoveries in membrane biology. Exploring these publications, even abstracts, exposes learners to current research trends. University websites often host open-courseware materials, providing lecture notes and assignments from advanced cell biology courses. Interactive simulations demonstrate passive and active transport mechanisms, enhancing visualization and comprehension. Finally, dedicated websites focusing on cell structure and function offer detailed diagrams and explanations.

Current Research in Membrane Biology

Ongoing research intensely investigates the plasma membrane’s dynamic role in cellular defense. Scientists are exploring novel mechanisms by which pathogens evade membrane-mediated immune responses, focusing on viral entry and bacterial toxin translocation. A significant area examines how membrane proteins, particularly receptors, trigger intracellular signaling cascades upon pathogen recognition.

Researchers are also studying the impact of membrane lipid composition on immune cell function and inflammatory responses. Investigations into endocytosis and exocytosis pathways reveal how cells internalize and eliminate threats. Furthermore, advancements in microscopy techniques allow for real-time visualization of membrane dynamics during infection. Studies are also exploring the potential of manipulating membrane properties to enhance drug delivery and improve therapeutic outcomes against infectious diseases and cancer, published in journals like Cell.